Electric mobility in South East Asia

My local copy of the same post as published on Medium. Medium Post is linked here.

Electric vehicles are disrupting two of the largest industries in the world — oil & gas and automotive. Electric vehicles have been around viably for 2 decades now, but the adoption rates are still low. Yes, periodically, we see new electric models being introduced by every major car company. We have also seen more than 90 Bn dollars of investment in 2018 alone worldwide into electric car R&D, manufacturing and start-ups, but something is still missing.

This is an opinion piece on how motorbikes should be the primary focus for electrification of transport, how good electric motorbikes already exist but how a good light electric vehicle infrastructure does not exist, thus hindering the much-needed adoption of electric motorbikes in South East Asia and the world.

Let’s start by taking a step back and looking at the transportation sector in the world. Globally, there are more motorbikes than any other type of motorized vehicle. Second come cars, then vans, buses, 3-wheelers, heavy transport, trains etc. Why is the automotive industry ignoring motorbikes? Though I understand the revenue per device and the investment requirement arguments, if we are truly looking to electrify transport, motorbikes need more focus than cars.

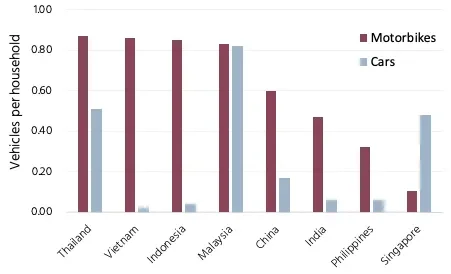

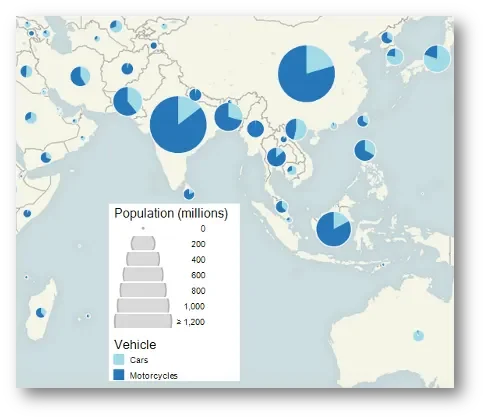

Specifically, in Asia, where 60% of the global population live, work and travel, motorbikes dominate transportation. In Vietnam, India, Indonesia and Thailand, motorbikes outnumber cars [Figure 1]. In fact, in most countries where GDP per capita is lower than world average, motorbikes to car ratio is very high [Figure 2]. One can think of half the world running on motorbikes. Given that motorbikes emit more greenhouse gases per person than cars, electrification of motorbikes becomes more urgent.

Figure 1.

Motorbikes outnumber cars in most South East Asian countries. (Source — collated from multiple sources by author)

Figure 2.

Lower GDP countries have higher motorbike to car ratio.

First, undeniably the motorbike market is huge. It is a market segment that is here to stay, with ownership models are not shifting towards a shared economy in this sector.

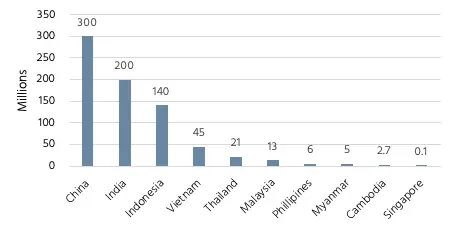

Let me take the example of Indonesia. There are 140 million bikes for a population of 270 million people. Considering that about 27% of this population is too young and 6% is too old to ride any vehicle, we are left with 180 million people potentially able to ride one. 140 million bikes among 180 million people means that more than three in every four potential riders/drivers own a motorbike each!

Average salaries in Indonesia are low and for many, buying a car is an unthinkable luxury. Even buying a bike is quite an undertaking. One would need to consider a hire-purchase and work out a 2- or 3- year payment plan with the dealership or a bank. Though statistics show a year-on-year growth in per capita income, for a vast majority of people owning cars is not in the cards for a while. Besides, taking an environmental perspective, with many South East Asian cities being low-rise and congested already, it would be unwise to introduce more cars anyway. The same holds true for most regions in the world.

People in South East Asia still prefer to own a vehicle rather than share one. South East Asia is a very price sensitive market. We look for the best bargain for every purchase we make. When shared mobility is introduced to this market, people here will do the math and quickly realise that owning a device with a good second-hand market value is worth the investment even if it involves taking a 2- or 3- year loan, compared to renting, leasing or sharing. I remember shopping with my mother and grandmother when I was a kid, watching them haggle on the price of everything, even tomatoes, even though we could afford it. This is who we are. I do not deny that there will be a growing niche of the population who will prefer the shared model for various reasons but for the vast majority, single ownership will still be the better option.

The same holds true for India, Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, Philippines, parts of China, most of South America and Africa. Indonesia is just an example. [Figure 3]

Figure 3. Number of motorbikes by country. (Source — collated from multiple sources by author)

Secondly, electric motorbikes are already here.

What is the alternative to petrol motorbikes? Good electric motorbikes. These already exist. The brands that come to mind are Zero, Niu and Gogoro, but there are quite a few other companies around the world who design, manufacture and are ready to sell electric motorbikes. Some of them are Vostok in Spain, Edison Motors in Thailand, Ather in India, Gesits in Indonesia, RedE in France and the list goes on. There is no shortage of manufacturers that produce electric motorbikes. Like petrol motorbikes, price parity, performance parity and abundance of options already exists.

Thirdly, with the above in mind, let us now look at what is needed to get electric motorbike adoption going.

When I talk to customers, the first question they bring up is — how do I charge my bike? This means infrastructure needs to be addressed along with introducing electric bikes to the market. If we continue to neglect that, as we do now, adoption will not happen. We need an infrastructure option that works for electric motorbikes.

What infrastructure exists today? We have the Combo 2 charger [Figure 4] which has been standardized with policies built around these chargers in many countries including Singapore. It is slowly being introduced in parking lots, homes and even petrol stations. The Combo 2 chargers deal with massive voltages and currents. For these to be effective, there needs to be a bulky converter within the vehicle and a large connection port. When we add this to motorbikes, they take up way too much space, probably about the same as the motor. It will add significant costs and complexity too.

Figure 4. Bulky Combo 2 charger. (Source — https://insideevs.com/news/333637/european-ccs-type-2-combo-2-conquers-world-ccs-combo-1-exclusive-to-north-america/)

The Combo 2 chargers are expensive to set up and are generally low utilization devices. Cars plug into them for 4–6 hours or overnight as needed. Imagine now a fleet of bikes that gets plugged into the same infrastructure, hindering use of these chargers by cars, or worse, having to setup much more of these chargers at every parking lot just to allow charging of bikes.

These chargers are great, but are they the best way forward for electric motorbikes? Let us look at electric motorbikes and try to figure out what is best for them. What do all electric motorbikes have in common? A small, manageable battery pack. Most electric bikes have battery packs of less than 4 kWh, which tends to weigh about 15 kg. These batteries can be handled by the rider easily. Also, a vast majority of the electric motorbikes are already built with removable and swappable battery packs — unlike cars with their humungous 600 kg battery packs, impossible for anyone to imagine handling themselves.

So, we have, on the one hand, expensive, bulky and complicated Combo 2 chargers, intrinsically low in utilization rate because of long charging times, and, on the other hand, electric motorbikes are built with simple, light, removable and swappable battery packs. With these, the obvious way forward would be battery swapping. Much like one would ride a petrol motorbike but, instead of stopping at a petrol station, you go to a vending machine [Figure 5], where one swaps the battery pack for a fully charged one in less than 1 minute. If this infrastructure is setup in convenient road-accessible locations, one can forget about range anxiety, charging time and other common infrastructure worries. Battery swapping is also much cheaper than petrol refill and provides a better experience than charging. It is a simple, above-ground, low-footprint solution and is significantly cheaper than setting up charging points everywhere.

Standardization of battery swapping is necessary too. There are IEC regulations now in the final draft phase for removable and swappable battery packs — IEC 61821. In later 2020 or early 2021 these will be ratified. As a thumb rule, standardization combined with strong government policy, tends to reduce costs since the market can finally focus on economies of scale. This also tends to increase safety and reliability.

In conclusion –

1. there needs to be more focus on motorbikes to truly electrify transport in the world,

2. good electric motorbikes already exist but their adoption is low because of lack of infrastructure and

3. a sensible infrastructure for light electric vehicles like motorbikes is battery swapping.

All these considerations form the rationale behind Reit EV, the energy infrastructure company that my co-founder and I started in 2019. It strives to enable mass adoption of electric motorbikes in South East Asia and the world. Being motorbike manufacturer agnostic, we have developed in-house an intuitive, fully automated battery swapping solution both hardware and software [Figure 5]. It is highly customizable and easily scalable. We have built our solutions in full compliance with international regulations, so our solution is future-proof as well.

Figure 5. Reit EV battery swapping solution.